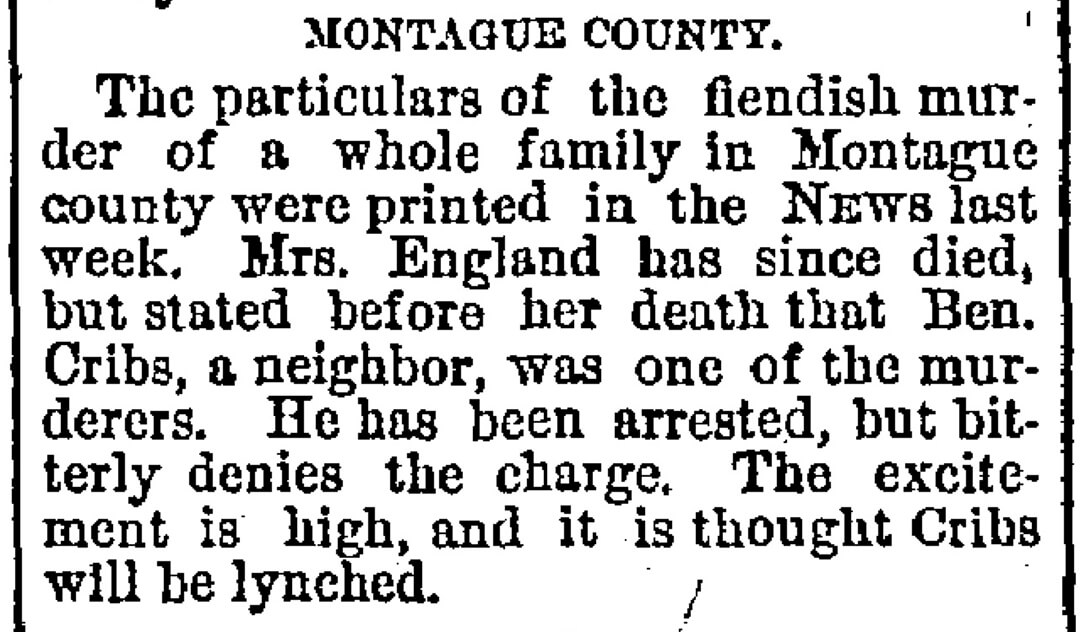

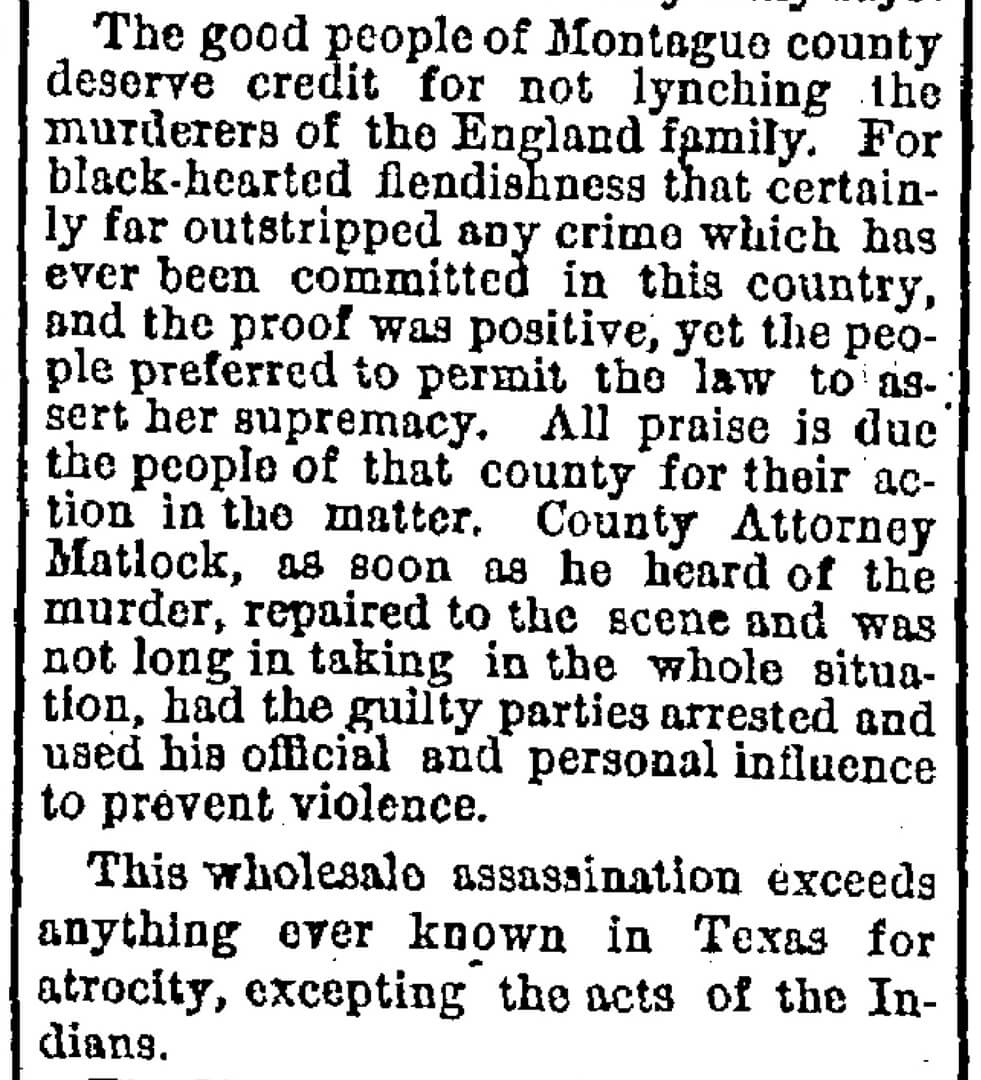

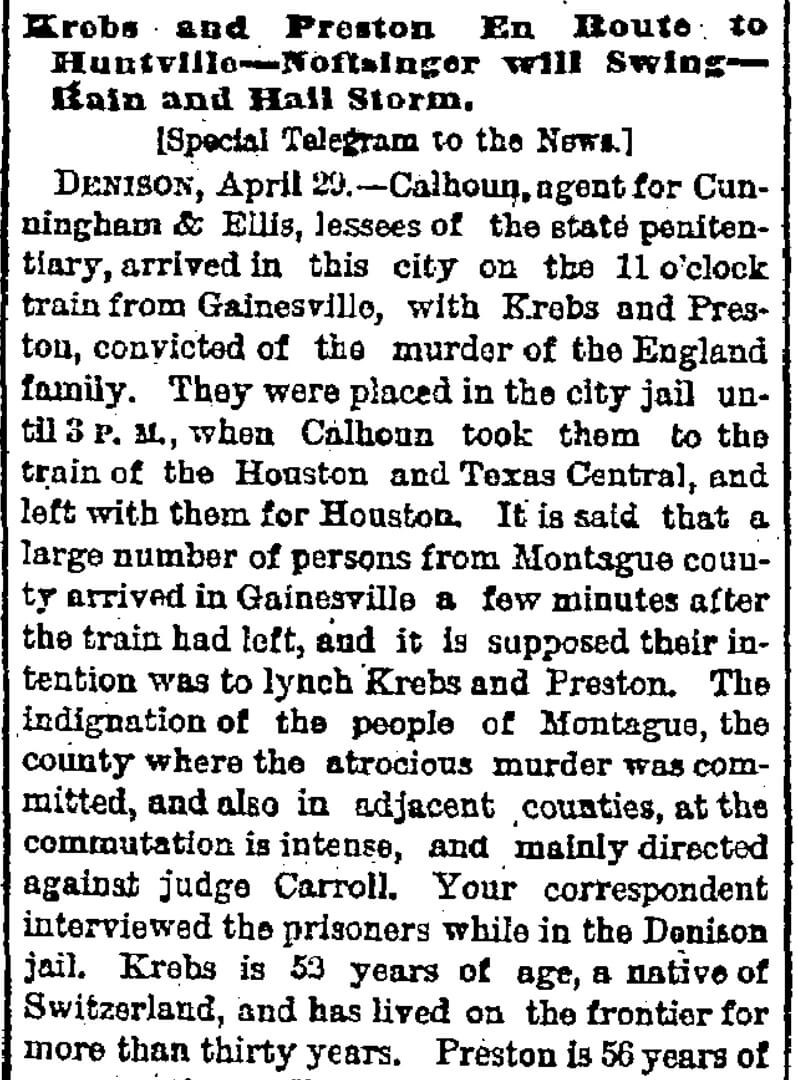

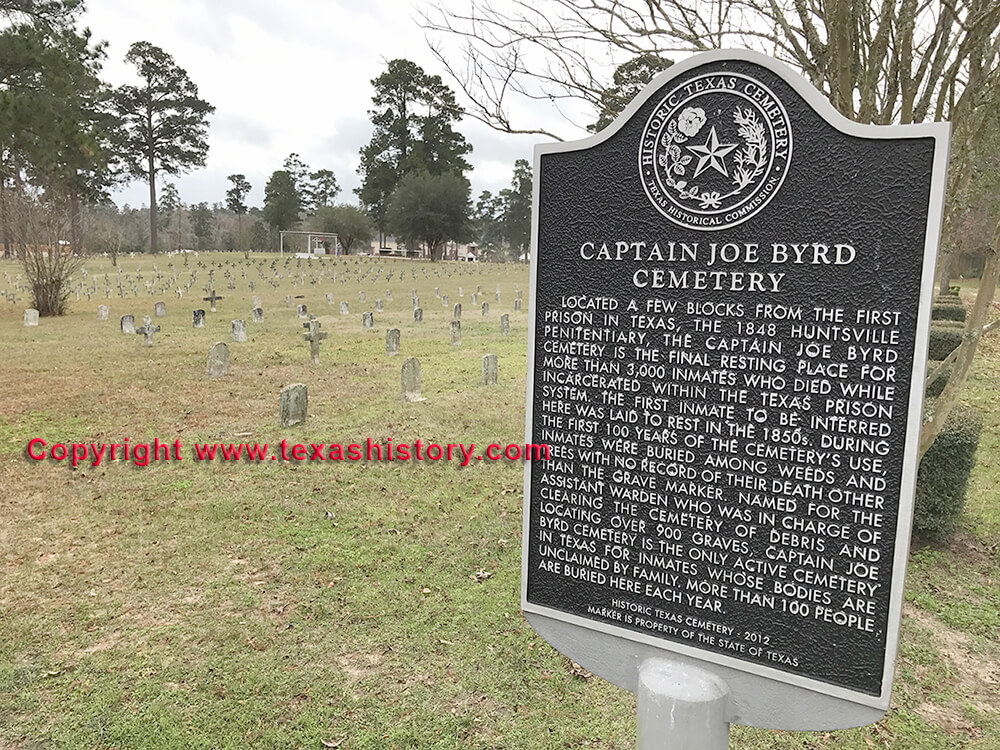

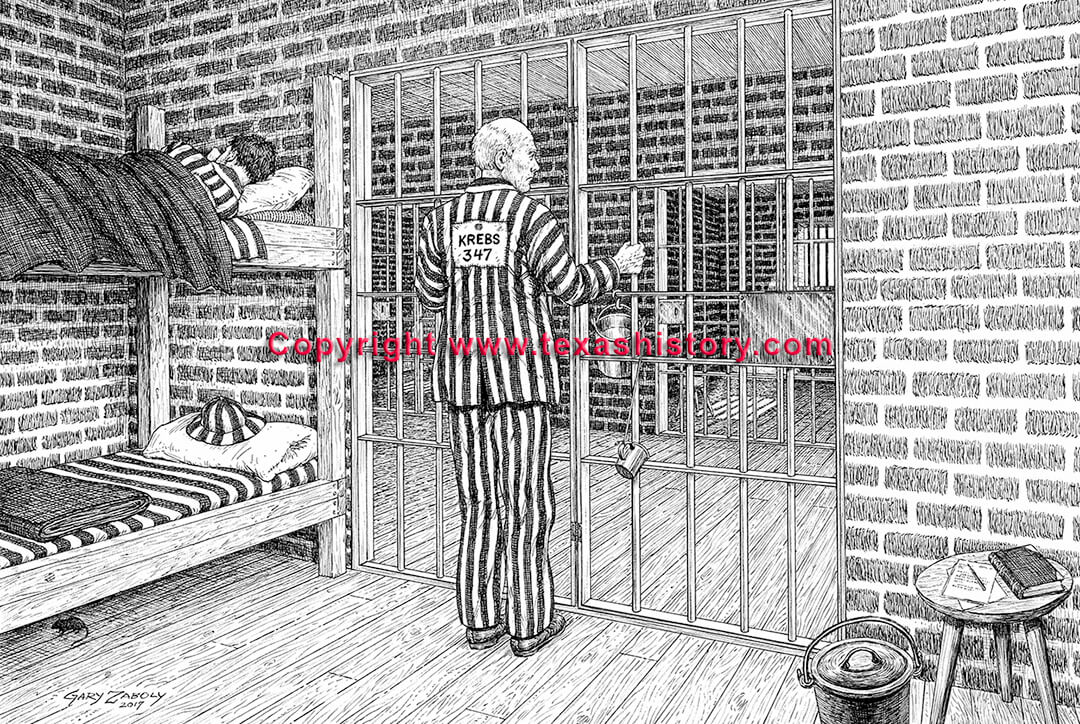

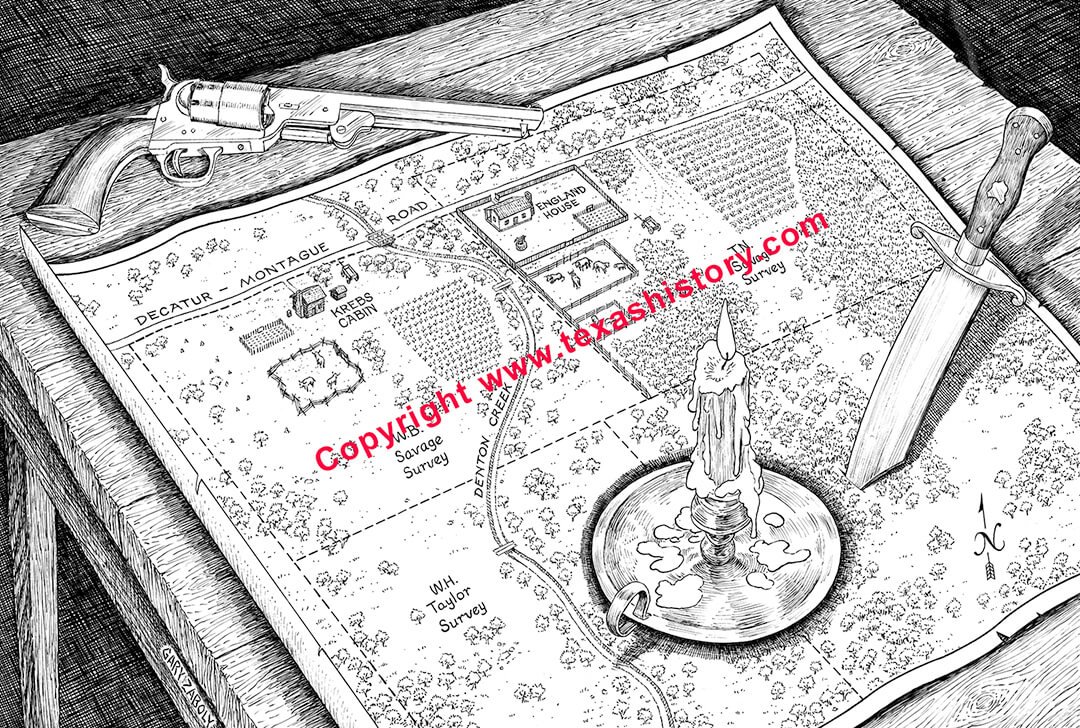

The England murder case spanned two decades. The legal aftermath involved five Texas governors, five trials at Montague and Gainesville, and five appeals to the Texas Court of Appeals. During this time, Ben Krebs and James Preston remained in prison, condemned to a life at hard labor. The two men continued to protest their innocence, claiming that others had committed the brutal slaughter of the England family. Over time, additional evidence came slowly to light. Locals in Montague County were fearful of speaking up, fearful of being lynched by local vigilantes allegedly in league with the county attorney. Finally, by the 1890s, some of them were willing to go on record with what they knew about the case.

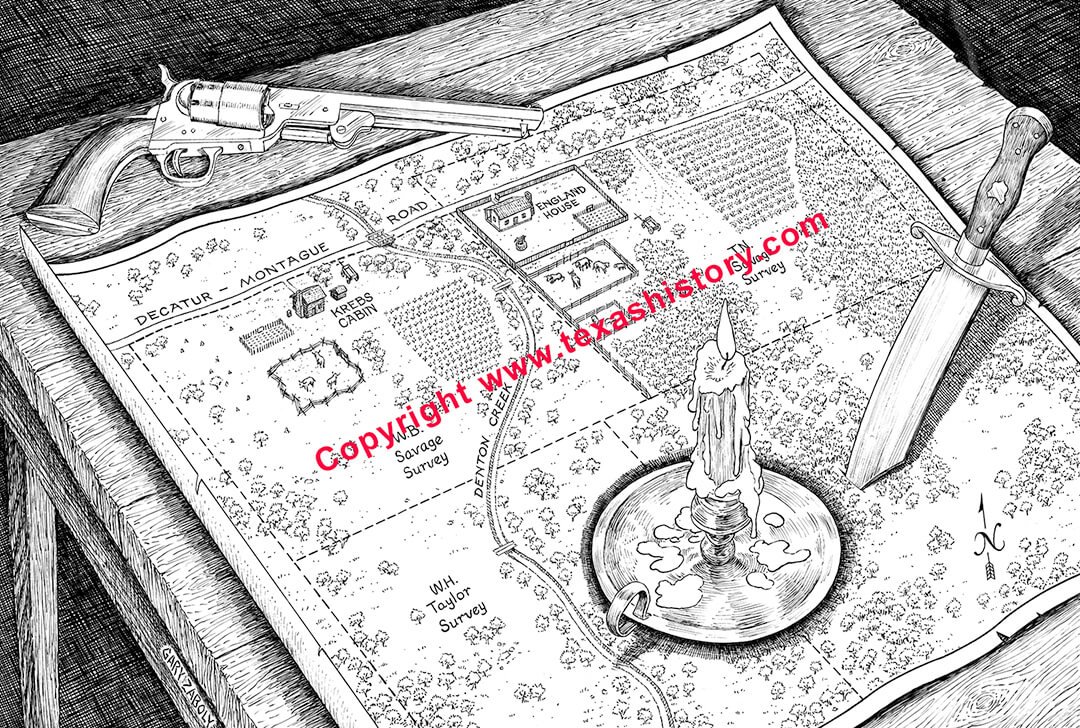

What was the truth regarding the England murders? Did Krebs, Preston, and Taylor kill the Englands or were they framed for a crime they did not commit? Were others responsible? It has been almost a century and a half since William England, Selena England, and two of her children, Susie and Isaiah, were murdered six miles south of Montague, Texas. Texas Governor James S. Hogg called the case “the strangest, most novel and peculiar . . . . The blackest pages of criminal justice do not portray or present a blacker nor more fiendish deed than the destruction of the England family.” For avid readers of mystery and true crime, the England murder case is full of numerous, fascinating plot twists and developments. For anyone interested in Texas and its legal history, the case offers a realistic snapshot of frontier justice and retribution in North Texas following the Civil War, as vigilante justice grudgingly gave way to an established system of law and order.

For an in-depth look at this compelling murder mystery, read Murder in Montague: Frontier Justice and Retribution in Texas, published by University of Oklahoma Press, and available on our secure online webstore. The book is also available at University of Oklahoma Press and Amazon.

For an in-depth look at this compelling murder mystery, read Murder in Montague: Frontier Justice and Retribution in Texas, published by University of Oklahoma Press, and available on our secure online webstore. The book is also available at University of Oklahoma Press and Amazon.

For an in-depth look at this compelling murder mystery, read Murder in Montague: Frontier Justice and Retribution in Texas, published by University of Oklahoma Press, and available on

For an in-depth look at this compelling murder mystery, read Murder in Montague: Frontier Justice and Retribution in Texas, published by University of Oklahoma Press, and available on