Today its size is under 100,000 acres. It’s hard to imagine that when the first pioneers came here in the early 1800s the Big Thicket of Southeast Texas covered three and a half million acres. Back in those days the borders of the Thicket were the Trinity River to the west and the Sabine River, which is now the Texas-Louisiana border, to the east. To the north, it was the old cattle or Beef Trail, that ran from Tyler County to Louisiana, and to the south, it was the Spanish Trail or the Atascosito Road, that parallels modern Highway 90 and Interstate 10 from Liberty to Orange, Texas. The first wave of homesteaders came here around 1820. Most of them were from the southern states of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. The vast majority of them were farmers. They avoided the heart or center of the Big Thicket, choosing instead to settle on the edges of this vast, primeval forest. To many early settlers, the Thicket represented the unknown, one could sense a sort or presence or power here. In the heart of the Thicket, the forest is tight and dense. In many parts of these woods, it’s impossible for a man to walk upright.

“There are places in these woods that you have to get down on your knees to crawl through. Someone said that it was so tight that if a snake went in, he’d have to back out. There around the edges though, it was tall yellow pine. These were pioneers that were looking for land of their own and looking for privacy. They were individuals that didn’t come to join the chamber of commerce. They were people who lived off the land and whatever they crops they could raise and whatever game they could hunt. They lived as close to the land as the Indians did.”

Dr. Francis E. Abernethy

“The early settlers didn’t want to go into the interior of the Big Thicket, the interior scared them, too dark, too thick, and too swampy. But later settlers who came in the 1830s moved on into the Thicket and carved out little farming areas for themselves. They cut down enough trees so that they could farm a piece of land and get enough food to last them a year from those crops. They were people who liked a remote life.”

Howard Peacock

The Anglo settlers who came here in the 1820s were not the first inhabitants of the Thicket. Native Americans had been living in the region for some time. The two major tribes in the Big Thicket were the Alabama and Coushatta Indians, who had migrated to Southeast Texas in the 1780s from Alabama and Louisiana. These two tribes have lived all over the Thicket, but they now share a common home here on their 4,300-acre reservation in Polk County. Tourism and energy exploration are the major sources of income today, but when the tribes first came to the Thicket they were known primarily as farmers and hunters. They actively hunted bear and deer, and fished in the streams and rivers. From the start, these Indians extended a helping hand to the white settlers. Sam Houston was counted as their close friend and the tribes helped many Anglo families in distress during the Texas Revolution. During the Civil War, twenty-one Alabama-Coushattas served the Confederacy.

James Sylestine

“The men and women would go on hunting parties together into the woods. While the men hunted, the women would work on their basketry, splitting cane and weaving the strands together into beautiful baskets. When they came back they would have a celebration, ballgame, dancing at night. Their ballgame was lacrosse, and that ball I understand used to go like a bullet.” While the Alabama and Coushatta adopted some of the white customs such as living in log cabins, they also kept many of their tribal rituals and customs intact. One of these was a sophisticated knowledge of the various medicinal properties of the surrounding trees, plants, and shrubs.

Howard Peacock

“They used about 60-70 plants native to the Big Thicket for their medicinal needs. It was a varied and rich medicinal lore that they passed on. For example, there’s a bush here called Strawberry Bush or Hearts a Bustin’ With Love, and that particular plant was used to make tea and the tea was given to women during childbirth to ease their pain.” The Alabama and Coushatta also loved to dance, although theirs was of their own variety and in keeping with their customs.

James Sylestine

“They danced all night long until early in the morning. The most beautiful of these dances was the Dove Dance. They all had a white cloth, handkerchief, or white feather, and they all had a white object in their hands, all waving, quite a beautiful, flowing dance. When the dancing was finished, the host always said, ‘it is at an end,’ and when that was shouted everyone took off, spread in every direction, and the host would have to catch somebody. When they catch someone and tag them, then they will be the person who will be the host next time.”

There’s a small spot in this depression where a black substance is oozing to the surface. If you poke about with a stick, you soon discover that it’s tar. Nearby is a puddle of water with an oily tint and smell to it. These are a few of the telltale signs left today of what was once the Sour Lake Springs Resort, the most famous health spa of the Big Thicket. This land in Hardin County was once dotted with mineral springs. The Indians were the first to bathe in these healing waters. By the 1840s, the area had quickly become a booming health resort. Soon the waters and the tar were being bottled and sold as cures for most any ailment, especially skin and digestive disorders. A magnificent 100-room hotel was built here and the Sour Lake springs soon became an exclusive resort.

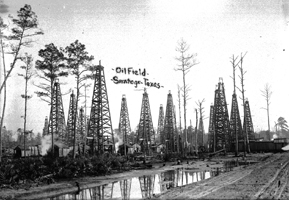

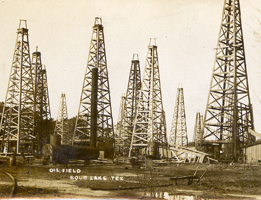

People lost interest in the health spa, but not in the seeps that spawned them. These oily seeps and tar were good indicators that something else was beneath the surface here. It all started in 1901 when the Spindletop Oil Boom blew in at Beaumont, twenty-five miles away. During this same year oil was discovered at Saratoga. At Sour Lake, one petroleum enterprise named the Texas Company tried their luck with two exploratory wells. They decided to try a third and in January 1903 they hit paydirt and the oil giant known as Texaco was born. One year later Batson came in and soon Hardin County had a huge oil boom on its hands.

Watch a sample video clip from our documentary

The Big Thicket of Southeast Texas: A History, 1800-1940

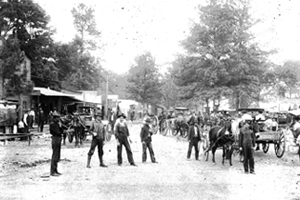

“The oil industry replaced the timber industry as the major economic activity, also in terms of wealth. It made millionaires overnight. The con men came in of course, they sold slivers of land. Overnight towns sprang up. Batson is an excellent example, essentially it was a prairie, mostly agriculture and ranching, and overnight it grew into a town of 10,000-12,000. These were not nice towns. They were not a community. They were for the roughnecks coming in to do the labor in the oil industry, drilling the pipes, setting up the storage areas, building the wooden derricks. There was a lot of fighting, a lot of gambling went on. Saloons were set up in an instant. And then they were gone as fast as the oilfield was produced. In the justice of the peace records from Batson, almost on a daily occurrence in the days, 1909-1910, behind these saloons they’d find someone who’d been knifed to death or shot to death. Violence was part of life in these rowdy boomtowns.”

Robert Schaadt

Perhaps the most famous outlaw of the Big Thicket was Red T.J. Goleman. Red robbed the Hull State Bank in Liberty County in July 1939. He later turned himself in, but then jumped his bail bond. For months he hid out in the Big Thicket, eluding lawmen. Red had grown up in Hardin County and knew these woods firsthand. Goleman would go out, commit a crime, and then dart back into the safety of the Thicket. Robbery, attempted murder, and assault, Red’s legend seemed to grow while he was in hiding. Parents would tell their children that if they didn’t behave, Red was going to come out of the Thicket and get them. A posse of lawmen finally cornered Goleman in an old corncrib in April 1940. Red supposedly refused to surrender and lawmen cut him down on a hail of bullets.

Years later, there’s still some controversy as to whether Goleman was the vicious criminal that lawmen made him out to be. Bill Brett & Jude Hart: “ They didn’t call him Red, they called him T.J., Thomas Jefferson, and the feeling I get and what I’ve been told, he was a good neighbor, if he could help anybody he would, a better citizen than what we got now, I’d rather trust him than some of these others. He didn’t have but one little fault and that was robbing banks. Now outside of that, you just couldn’t ask for a better citizen.” Most of the $12,000 taken in the Hull Bank robbery was never recovered. The story goes that Red hid it somewhere in the Thicket.

Despite all the changes over the years, some of the flavor and character of the old Thicket remains, thanks largely to the creation of a national preserve here in October 1974. As long as these woods remain standing in this preserve, there will always be a Big Thicket, both in legend and reality. Jude Hart & Bill Brett: “Yeah, you take right out here where we live, we like company, but I guess we just get along better if we’re out by ourselves. You just don’t want nobody crowding you, pushing and shoving you. Bill lives off by himself and I do too, we don’t want nobody meddling with us, I guess we’re selfish, contrary, whatever you call it, you’re welcome if you come, if he drives up here and we know him and know he’s coming, glad to make them coffee or feed them, whatever, but really and truly, don’t come crowding, don’t come pushing.”