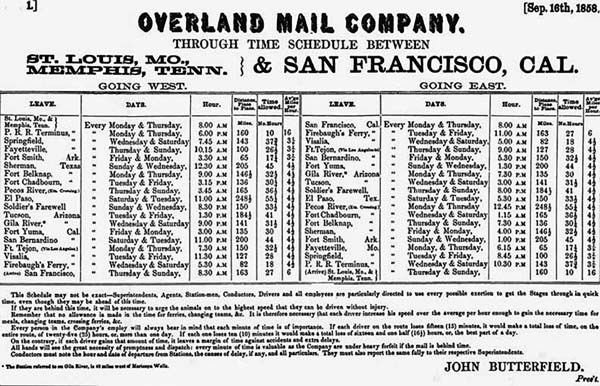

2008 marked the 150th anniversary of the Butterfield Overland Mail’s maiden trip from St. Louis to San Francisco that linked America’s East and West together for the first time. One-fourth (740 miles) of this 2800-mile road that connected the nation ran through Texas. During 2008, TexasHistory.com will bring you authentic and exclusive snapshots of pre-Civil War life along the Butterfield trail in Texas. Our vignettes are special, we tell you the human story of life in Texas along the Butterfield Overland Mail, the inside Butterfield history that you will only find here at TexasHistory.com.

We start our 150th anniversary trip at Colbert’s Ferry the Butterfield’s gateway into Texas, situated on the banks of the Red River, which separates Oklahoma (known as Indian Territory in 1858) and Texas. We hope you enjoy our unique Butterfield snapshots. Please check back throughout 2008 to see more of these personal and close-up stories of life in Texas along the Butterfield Overland Mail, available only at TexasHistory.com, your source for Texas History. You can also learn about another portion of the Butterfield Overland Mail in far West Texas by viewing previous history pages in our archives at TexasHistory.com.

To read the history of the Butterfield Overland Mail in Guadalupe Mountains National Park, please click on this link.

Additional history on about the Butterfield Overland Mail and its stage stations in the Guadalupe Mountain region of Texas’ Trans-Pecos can also be found in our documentary A History of the Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns, 1840-1940. For more information on this documentary, please click on this link.

The Butterfield Overland Mail In Texas 150th Anniversary Commemoration At TexasHistory.com

Installment One: Colbert’s Ferry-The Gateway To Texas

Looking across the Red River into Texas from the Oklahoma shoreline, the tranquil, idyllic setting belied the racial, cultural, and ideological divisions simmering on a low boil throughout the region. North Texas in 1858 was a ticking time bomb set to explode. When the Overland Mail Company commenced operations in the Lone Star State that year, several factors were already combining to ensure the destruction of the route less than three years later. Grayson County, on the south bank of the Red River, and its neighboring county to the west, Cooke County, encompassed a chaotic mix of disparate elements. The region was the point in Texas where the Old South and the American West converged. Fire-eater secessionist slaveholders encountered ranchers and farmers who owned few slaves and a number of whom favored keeping Texas in the union. Strong and divergent opinions mixed and interacted, and not always peacefully. In 1858, much of the area was in a raw, frontier state, largely undeveloped and with few cities. Chronic raiding of the outlying communities by Kiowa and Comanche Indians kept residents on edge, never knowing when or where the next depredation would strike.

The pioneers’ anxieties reached a feverish pitch on October 16, 1859, when radical abolitionist John Brown attacked the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, intent on fomenting a violent slave insurrection. Pro-slavery residents of the North Texas Red River country worried that John Brown types might soon infiltrate their communities and stir up dissension. Two days before John Brown’s raid, trouble was already brewing in Cooke County. In Gainesville on October 14, 1859, citizens passed a resolution calling for an investigation of possible abolitionist intrigues in the country. The source of citizen concern was a letter belonging to George Humphrey, a Butterfield stage driver from New York. In the spring of 1859, the Cooke County grand jury convicted Humphreys of “gaming with a negro slave.” Humphreys left quickly thereafter, but gave some of his letters and personal effects to a local resident for safekeeping.

In one letter, E.C. Palmer, a Gainesville resident recently moved from Marshall, Texas, wrote to the Overland Mail employee using incendiary language. Palmer spoke of an impending civil war, and of Northerners needing to get practice in fighting Southerners. Cooke County residents attending the emergency meeting heatedly declared themselves united in their opposition to secret Northern organizations, whose “ultimate design” was “to strike a decisive blow at that peculiar institution of the South-slavery.”1

North Texas succumbed to a full-scale slave revolt panic after a series of fires broke out in Dallas, Denton, and Pilot Point nine months later in the summer of 1860. Convinced that persons sympathetic to John Brown or Nat Turner (who in 1831 led a failed slave revolt in Virginia) set the fires to spark an insurrection, local vigilance committees killed between 30 to 100 people, both black and white. Area law enforcement officials looked the other way as lawless brigands carried out their bloody work.

Vigilantes in Fort Worth hung alleged abolitionist William Crawford in July 1860, and a few months later, on September 13, 1860, strung up anti-slavery Methodist minister Anthony Bewley from the same tree. Left dangling from the limb, locals finally cut down the minister the following day and buried him “in a shallow grave. Three weeks later his bones were unearthed, stripped of their remaining flesh, and placed on top of Ephraim Daggett’s storehouse, where children made a habit of playing with them.” Bewley’s lynching left his wife and eight children destitute, forcing them to fend for themselves. The September 13, 1860, issue of the inflammatory, aptly titled Jacksboro White Man, offered its grisly congratulations to Bewley’s assailants, saying, “Good lick.”2

Subsequent studies of the so-called “Texas Troubles” of 1860 show that no concrete evidence existed of any wrongdoing by those lynched. Donald Reynolds writes, “But the damage had been done. Southern-rights extremists in Texas and throughout the South made skillful use of the Texas Troubles in fire-breathing speeches and editorials to whip up secessionist sentiments.” While many Texans previously supported Governor Sam Houston’s moderate unionist policy, the slave insurrection panic of 1860 pushed a significant number of the state’s moderates firmly into the secessionist camp.3

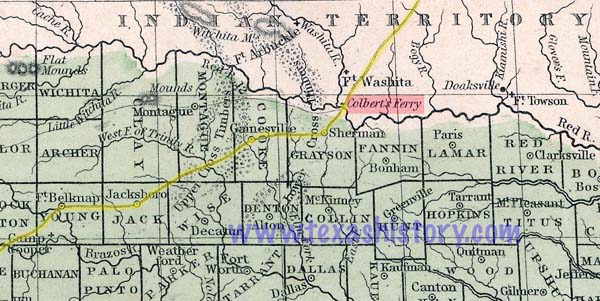

Such is the situation the Overland Mail Company found itself facing in Texas as it sent its first coach westward in September 1858. The particulars of Butterfield’s contract with the Postmaster General called for stagecoaches to cross into Texas at or near Preston, in far northern Grayson County. Intense lobbying of government officials in the nation’s capital by residents of Sherman and McKinney succeeded in moving the entry point to Colbert’s Ferry and re-routing the road through Sherman. Albert D. Richardson, traveling westward on the Butterfield in September 1859, said he crossed into Texas at Preston, but he was mistaken. Early Butterfield timetables also listed Preston, but the mail company’s first westward coach crossed at Colbert’s Ferry on September 20, 1858.4

Preston was a major Red River crossing from 1846 to 1850, with almost 1,000 wagons using the crossing in a one-year period. By 1858, Preston was in serious decline.

The U.S. Army supply depot there closed in 1853, after only eighteen months of operations. Silas Colville and Holland Coffee’s trading post formed the nucleus of the community. In its heyday, Preston enjoyed the reputation of “a ribald, boisterous, and profane frontier town and a frequent destination of Indians seeking liquor.” A fracas in Preston in October 1846, led to Holland Coffee’s murder. Randolph Marcy’s emigrant road to California, which led westward across North Texas’s Peter’s Colony, originated here, and the Shawnee Trail crossed the Red River at this point. The growth of communities such as Sherman and McKinney, however, siphoned commerce and traffic away from Preston, and by the end of the 1850s, the town’s heyday passed. Today the townsite lies under Lake Texoma, constructed in 1944.5

Standing on the Texas side of the Red River, seven miles downstream from Texoma and gazing across to Colbert’s Ferry in Oklahoma, the important role this now-obscure crossing played prior to the Civil War gradually dawns upon the visitor. This ferry served as the nation’s official gateway in and out of Texas. To an observer in 1859, sitting on the rust-colored beach, the spectacle of the diverse parade of personalities, races, and cultures making their way up and down this muddy red riverbank was assuredly a moving sight to behold. From 1842 to 1872, this section of North Texas served as one of the major entry points into the Lone Star State.

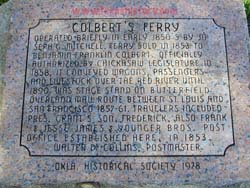

Directly across the river on the north side in Oklahoma, along a peaceful, tree-lined country road, sits the entrance to the Colbert’s ferry property. Joseph G. Mitchell built the first ferry here in 1842, but died just five years later.

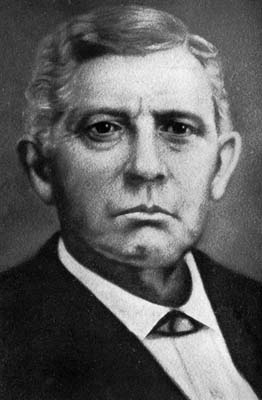

When Benjamin Franklin Colbert, a Chickasaw Indian, purchased the property in 1849, he hired Pennsylvania-native Joseph Bonaparte Earhart to make improvements on Mitchell’s previous ferry operations. Earhart later became personally involved in the Butterfield line, managing a stage station to the west at Hog-Eye Prairie, on the Jack-Wise county line.

In 1858, Colbert obtained a license for a toll ferry from the Chickasaw Legislature. Two years later, in 1860, he encountered problems with the owner of the ferry landing across the river in Texas, M.A. McBride. McBride wanted a piece of the ferry business, and in resolving the dispute, forced the Native American to purchase his property. Colbert’s Ferry was a stage stand on the Butterfield Overland Mail from 1858-1861, and carriages, wagons, and livestock crossed here until 1893. Travelers passing through here included Frederick Grant, son of Ulysses S. Grant, as well as Frank and Jessie James and the Younger Brothers.6

William Tallack, an Englishman making the trip eastward in the summer of 1860, arrived at the Red River crossing at sunset: “We entered the dark and tangled jungle which for many miles skirts the Red River. The trees hereabouts are festooned with wild vines, bright convulvi, and crimson trumpet flowers. The scene was a mixture of forest, garden, swamp, vineyard, hopyard, and jungle all in one.” Tallack described the road to the ferry as primitive, with old tree stumps protruding throughout. A stretch of a log corduroy road kept the coach from miring in the muck, but incessantly jolted the passengers. When the stage reached the riverbank, a crew of Colbert’s slaves ferried it across to the Oklahoma side. Tallack mentioned eating dinner at Colbert’s in a large log house.7

Waterman Ormsby, correspondent for the New York Herald, and the only through passenger on the Butterfield’s maiden westward run, arrived at Colbert’s on September 20, 1858, just before ten in the morning. After a good meal, Ormsby wrote, “Mr. Colbert, the owner of the station and the ferry, is a half-breed Indian of great sagacity and business tact. He is a young man, not quite thirty, I should judge, and has a white wife-his third.” The Herald reporter continued, “He is nearly white, very jovial and pleasant, and altogether, a very good specimen of the half-breed Indian.” Orsmby noted that the ferry keeper owned twenty-five slaves, utilizing them to lessen the steepness of the mail road’s grade on both sides of the Red River. The slaves also ferried the stage passengers across to the Texas shore on a raft, using poles to move the vessel.

By 1858, Colbert cleared $1,000 a year on his ferry operations, no small sum for the period. One of the Chickasaw Indian’s slaves, Kiziah Love, lived at Colbert’s Ferry when it was a Butterfield stage stop. She remembers that “Master Colbert run a stage stand and a ferry on Red River and he didn’t have much time” to supervise farm operations and his slaves.” Love says Colbert had “lots of land and lots of slaves. His house was a big log house, three rooms on one side and three on the other, there was a big open hall between them. There was a big gallery clean across the front of the house. Behind the house was the kitchen and the smokehouse. The smokehouse was always filled with plenty of good meat and lard.”8

The stage station here was a double-log cabin, with a dogtrot hallway in between, connecting the two structures. Two brick and stone chimneys were on either end of the cabins. The main room in each building measured seventeen by seventeen feet, and the connecting hallway was twelve feet long. Each cabin also featured a room on its backside; one, a shed and sleeping area, the other the dining room. Colbert also attached a kitchen to the side of the dining room, keeping it separate because of the fire danger.

After the Civil War, the Chickasaw Indian erected a larger, more refined home on the site, representative of his increased material success and prominence in the community. This building, named “Riverside,” burned and later the family built a third, smaller and more modest wooden house on the property. Colbert operated the ferry here for more than forty years, from 1849 until his death in 1893.9

Colbert’s family came to Indian Territory from the South as part of President Andrew Jackson’s Indian removal program in the 1830s. The Chickasaws, like the Cherokees and other members of the Five Civilized Tribes, believed that by assimilating the white man’s culture they would finally gain acceptance and respect in nineteenth-century America. A number of industrious and prosperous Indians like Colbert sported fine clothing and built large, elaborate homes. In their attempt to cultivate the wealthy southern planter image, Colbert and other Native Americans even acquired slaves. The 1860 federal slave schedule for the Chickasaw District of Panola County in Indian Territory shows that

Benjamin Franklin Colbert owned twenty-six slaves. Colbert slave Kiziah Love says, “That was a sorry time for some poor black folks but I guess Master Frank Colbert’s . . . [slaves] was about as well off as the best of ’em . . . Frank Colbert, a full-blood Choctaw Indian, was my owner . . . My Mistress’ name was Julie Colbert. She and Master Frank was de best folks that ever lived. All the . . . [slaves] loved Master Frank.” Love says the Colberts “let us do a lot like we pleased jest so we got our work done and didn’t run off.” Comparing her masters to white slave owners, she says, “I don’t expect we could of done that way iffen we hadn’t of had Indian masters.” Even though southern whites forced Chickasaws like Colbert to relocate to Indian Territory in 1837-1839, many Native Americans still emulated their former planter neighbors in the Deep South. Despite all their efforts at assimilation, these Indians never gained the acceptance and respect they so greatly desired. Whites such as Ormsby still viewed them as “nearly white, a good specimen for a half breed.” Ironically, these long-oppressed Indians, in trying to overcome Anglo prejudice and acquire status, in turn oppressed African Americans, using them as slaves on their farms and ranches. Native American assimilation efforts first in the South and later on the frontier invariably ended in frustration and heartache.10

Besides B.F Colbert’s, the other graves at the ferry site include those of his children Sarah and B.F. Jr., who died at ages 17 and 16 respectively. Colbert married four times in his sixty-six years. His last wife, Anna Colbert, the only one to outlive her husband, laid him to rest at the station site in 1893. Family members also buried Colbert’s younger brother, Henry Clay “Buck” Colbert, born in 1832 and later the Panola County Chicaksaw Nation constable, underneath a large tree on the property. Kiziah Love, B. F. “Frank” Colbert’s slave, recalled, “Master Frank had a half brother that was as mean as he was good. I believe he was the meanest man the sun ever shined on. His name was Buck Colbert.” Love says, “He was sho’ bad to whup [slaves] . . . he’d beat ’em most to death.” She remembers that, “Master Buck kept on being bad till one day he got mad at one of his own brothers and killed him. This made another of his brothers mad and he went to his house and killed him. Everybody was glad that Buck was dead.” Love’s account of Buck Colbert’s death conflicts with an 1858 newspaper article noting that Fiera Train killed Panola County sheriff H.C. Colbert with a shotgun blast at Preston, Texas when the two fell to quarrelling after sharing Train’s whiskey.11

Numerous pieces of dressed, cut rock from the old Butterfield station foundation litter the site today. There also is an antique cistern with a sundial lid. Over a six-decade period, the current landowner collected a remarkable variety of artifacts from the stage stop. Their collection includes pre-Civil War pistol balls, blue and white marbles, old mule shoes, trace chains, singletrees, doubletrees, spikes, square nails, skillet, hand-forged drill bits and other period tools.

A local old-timer, Mr. Holder, told the landowner about a double hanging he witnessed before 1900 on the Colbert property. Holder and his father, riding to church, saw two men, one Hispanic and the other a tall red-headed Anglo, hanging from an old live oak near the county road at the edge of the Colbert homestead. On their way home after church, the father and son noticed that someone cut the two men down from the tree’s bough. The Holders later learned that vigilantes caught the pair stealing three horses. The live oak still stands today, known to old-timers as the Hanging Tree.12

Colbert’s Ferry on the Red River was a third of a mile below the stage stop. The mail road ran southwest from the station’s log cabin, down a gradually sloping hill to the water’s edge. Today underbrush chokes the route down the hillside to the Red River, but the old trace is still clearly visible. The Oklahoma riverbank evinces a depression even now, marking the crossing’s distinct channel almost 150 years after the overland mail. Pieces of antebellum china and beer bottle glass poke up through the sand and mud bank. From the ferry in Indian Territory, it was 720 feet across the river into Texas. In 1875, Benjamin F. Colbert built a toll bridge almost half a mile upriver from the old Butterfield crossing, at a cost of $40,000. The Red River flood of 1876 knocked out the bridge and all of Colbert’s investment. The raging floodwaters also swept away a second steel bridge, constructed in 1892. A third and final toll bridge, erected in 1915, remained in operation until 1931 when a free bridge opened two-thirds of a mile feet upstream from the Butterfield ferry, and adjacent to the 1872 MKT-Katy railroad bridge. Today all that remains of the old toll bridge are the overgrown approaches on the Texas and Oklahoma sides, and the broken support pilings, which still span the waterway. Over on the Lone Star shoreline a fine, broad trace of the Butterfield Road leads to a ledge overlooking the river channel. Here the trail makes a wide cut into the bank, running straight down to the river. A sample survey of the south bank ferry landing site in 2002 produced several period bullets and a hand-forged iron screw. Thanks to the current owner’s excellent stewardship, Texas’ historic Red River gateway remains in excellent condition.13

Many thanks to Joe Reid Allen and Patrick March Dearen for all of their help on this Butterfield project, including their talented field research. Additional thanks to Donna Hunt.

COLBERT’S FERRY: THE GATEWAY TO TEXAS

COPYRIGHT 2008

ENDNOTES:

1 Dallas Herald, October 26, 1859 (quotations one and two).

2 Donald E. Reynolds. “Texas Troubles,” (Texas State Historical Association, The Handbook of Texas Online, hereafter cited as TSHA), http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/ handbook/online/ articles/view/TT/vetbr.html (accessed April 30, 2005), (quotation one); Rick McCaslin, Tainted Breeze: The Great Hanging at Gainesville, Texas 1862 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994), 24; Donald E. Reynolds. “Bewley, Anthony,” (TSHA) http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/ online/ articles/view/ BB/fbe71.html (accessed April 30, 2005), (quotation two); Rupert N. Richardson, The Frontier of Northwest Texas, 1846-1876 (Glendale: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1963), 235 (quotation three).

3 Donald E. Reynolds. “Bewley, Anthony,” (TSHA) http://www.tsha.utexas. edu/handbook/online/articles/view/ BB/fbe71.html (accessed April 30, 2005).

4 Albert D. Richardson, Beyond The Mississippi (Hartford: American Publishing Company, 1867), 225.

5 Morris L. Britton. “Preston, Texas,” (Texas State Historical Association, The Handbook of Texas Online), http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/ articles/view/PP/ hlp52.html (accessed July 14, 2004).

6 Morris L. Britton. “Colbert’s Ferry,” (TSHA), http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/ online/ articles/view/CC/rtc1.html (accessed July 14, 2004); Oklahoma Historical Society, “Colbert’s Ferry” marker at Colbert homestead, dated 1978.

7 William Tallack, The California Overland Express: The Longest Stage Ride in the World. Los Angeles: Historical Society of Southern California, 1935, 55.

8 Waterman L. Ormsby, The Butterfield Overland Mail, ed. Lyle H. Wright and Josephine M. Bynum (San Marino: The Huntington Library, 1942), 34 (quotation one), 35 (quotation two); T. Lindsay Baker and Julie Baker, The WPA Oklahoma Slave Narratives (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996), 258 (quotation three). Oklahoma Historical Society, “Colbert’s Ferry” and “Colbert’s Toll Bridge” markers at Colbert homestead, dated 1978 and 1958.

9 Roscoe P. Conkling and Margaret B. Conkling, The Butterfield Overland Mail: Volume One (Glendale: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1947), 278-287; Information on the Colbert family comes from the following sources: (CensusFinder.Com), http://www.censusfinder.com/oklahoma2.htm (accessed January 29, 2005); (RootsWeb.Com), http://www.rootsweb.com/~cenfiles/it/1860/index/ free/indx02.txt, http://www.rootsweb.com/~cenfiles/it/1860/index/slave/sindx04.txt (accessed January 29, 2005).

10 T. Lindsay Baker and Julie Baker, The WPA Oklahoma Slave Narratives (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996), 257 (quotation one), 258 (quotation two), 257-258 (quotation three). Chickasaw Indian removal discussed in: Muriel H. Wright, “Historic Places on the Old Stage Line from Fort Smith to Red River.” Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. 11, No. 2 (June, 1933); Mary E. Young, “Conflict Resolution on the Indian Frontier,” Journal of the Early Republic, Vol. 16, No.1 (Spring, 1996), 13; “The Cherokee Nation: Mirror of the Republic,” American Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 5 (Winter, 1981), 506-507; Waterman L. Ormsby, The Butterfield Overland Mail, ed. Lyle H. Wright and Josephine M. Bynum (San Marino: The Huntington Library, 1942), 35 (quotation four).

11 Colbert genealogy information from: K.M. Armstrong. “Descendants of James Logan Colbert,” (ChickasawHistory.Com), http://www.chickasawhistory.com/colbert/ i0005861.htm (Holmes Colbert) (accessed July 16, 2004); K.M. Armstrong. “Descendants of James Logan Colbert,” (ChickasawHistory.Com), http://www. chickasawhistory.com/colbert/ i0001287.htm – i1115b (Martin Colbert), http://www. chickasawhistory.com/colbert/ i0001982.htm – i1982 (Benjamin Franklin “Frank” Colbert), http://www. chickasawhistory.com /colbert/i0001115.htm – i1115 (Henry Clay “Buck” Colbert), (accessed July 14, 2004); T. Lindsay Baker and Julie Baker, The WPA Oklahoma Slave Narratives (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996), 259 (quotations 1 and 2), 259-260 (quotation 3). H.C. Colbert’s death reported in the Dallas Herald, July 1, 1858. Benjamin Franklin Colbert’s four wives were: Martha, who died in 1851, Malinda, who died in 1853, Georgia, who died in 1869, and Anna, who lived until 1927.

12 Landowner interview-Oct. 24, 2001; Field trip to Colbert’s Ferry, Oklahoma-Oct. 24, 2001; Second field trip to Colbert’s Ferry, Oklahoma-Jan. 29, 2002.

13 Information on the history of Colbert’s ferry comes from: Morris L. Britton. “Colbert’s Ferry,” (TSHA), http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/view/ CC/rtc1.html (accessed July 14, 2004); Red River Railroad Museum, “Red River Railroad Museum,” http://www.denisontx.com/railroad/museum.htm (accessed July 14, 2004); Additional information concerning Colbert’s Ferry comes from: Landowner interview-Oct. 24, 2001; Field trip to Colbert’s Ferry, Oklahoma-Oct. 24, 2001; Second field trip to Colbert’s Ferry, Oklahoma-Jan. 29, 2002.