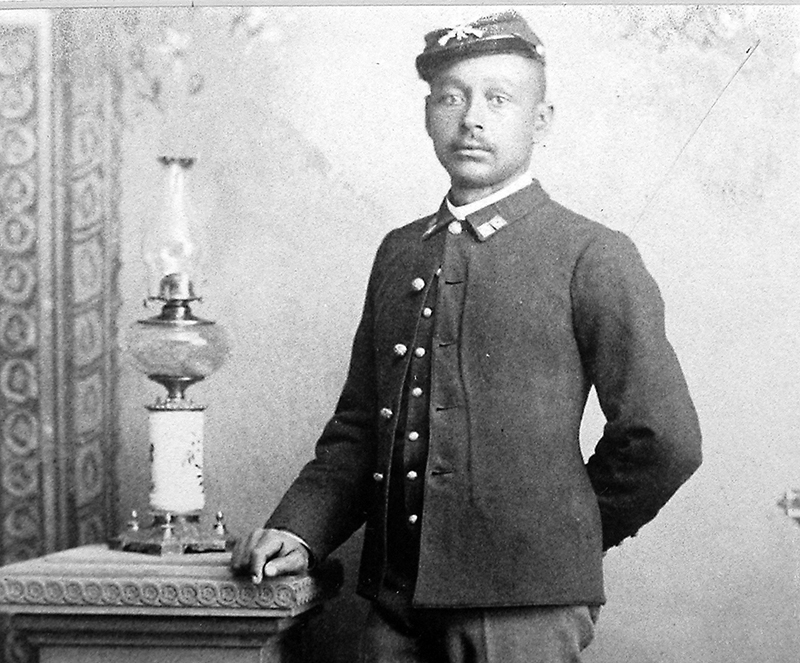

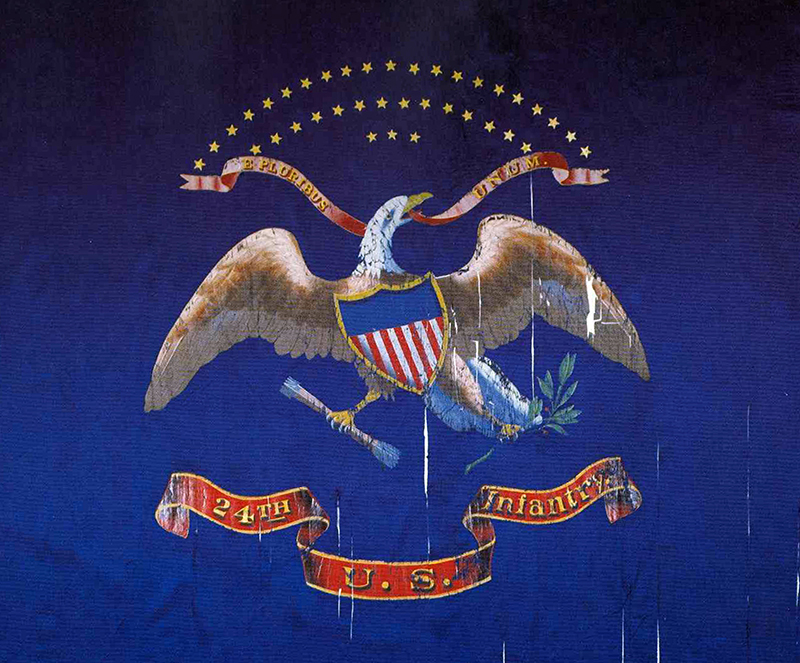

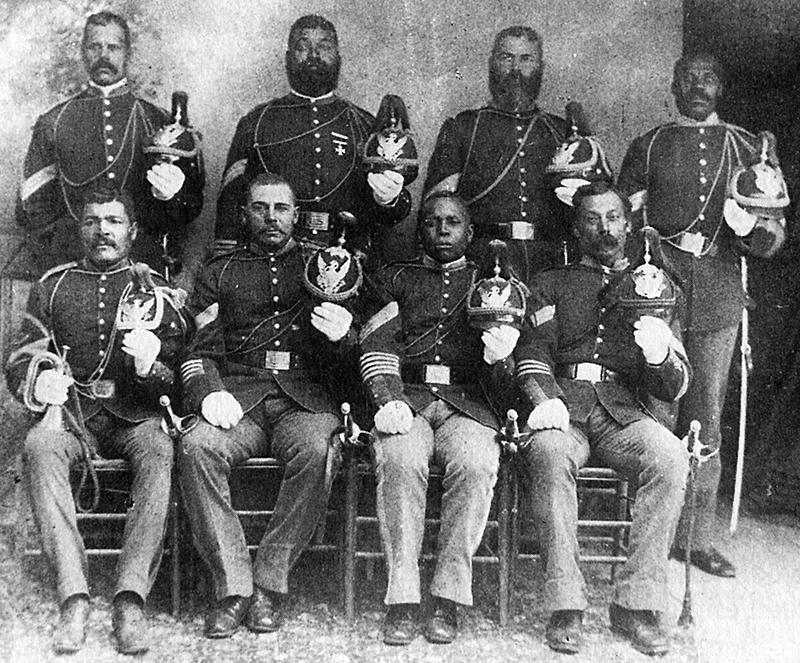

After the Civil War, Congress introduced a new presence, the buffalo soldier, to the federal army on the Texas Frontier. All four of the black regiments, the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry, and the 24th and 25th Infantry, saw duty in the Lone Star State. Many Americans did not favor having blacks in uniform. White officers reluctantly commanded black regiments, fearing it would ruin their careers. For African Americans, the military represented one of the few options in a racist and closed society in which they could earn a measure of respect and honor.

The buffalo soldier legacy is a bittersweet one. Despite their much-noted bravery under fire and the lowest rates of drunkenness and desertion, society refused to acknowledge the black units’ accomplishments. By 1900, Jim Crow legislation throughout the South disfranchised them of the rights and recognition they fought so hard for over three decades to obtain. Works by historians since the 1970s are helping to restore these African Americans to their well-deserved place in the story of the army in post-Civil War West Texas.

Military service in the West was one of the few places in post-Civil War America where blacks could prove themselves. The buffalo soldiers’ disciplinary, desertion, and performance records far exceed those of fellow white soldiers.

Despite this, only a handful of blacks in military service received the Medal of Honor. Often outperforming their white counterparts, the black regiments never earned the respect they deserved. Many western communities owed both their existence and survival to the notable services rendered by these black soldiers, but few settlements appreciated the hard work and dedication of these troops. A number of Texas communities experienced violent confrontations between white townspeople and black soldiers. Local law enforcement officials and juries sided with the Anglos during these incidents. Prejudice was one barrier African-American troops could not surmount.

Because of an acute labor shortage on the frontier, soldiers’ duties were often more akin to a common laborer. In addition, the very people whom the black troops protected often made their work unpleasant. Stage drivers, whom the buffalo soldiers were assigned to escort, disobeyed army orders to supply the black troops with food and lodging, and denied them passage on their stagecoaches. Without military escorts, the coaches were easy prey for the Indians, yet the anglo stage drivers harrassed the very people saving their lives. Despite these many challenges, buffalo soldier historian Arlen Fowler notes that, “the black regiments had an esprit de corps that was often missing in white regiments.”

(Arlen F. Fowler. Black Infantry in the West: 1869-1891. Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996, p. 32).

Opinions concerning the buffalo soldiers were directly related to the degree of contact one had with them. Those who served with the black troops often found their negative preconceptions changed. There are many accounts of the strong ties and mutual admiration that developed between white officers and their black troops. Despite this, many white stereotypes about African Americans died hard. One example of this was the belief that, being originally from Africa, black troops were better suited to the blazing Texas heat than the frigid Montana frontier. In both Texas and Montana, the buffalo soldiers soon proved they could serve with distinction, no matter the climate or the posting.

While whites have been largely ignorant of the vital service provided by these brave men, historian Arlen Fowler notes that members of the black community have, for many years, looked to the buffalo soldiers for inspiration. Quoting Rayford Logan, an African American Professor at Howard University, “Negroes had little at the turn of the century to help sustain our faith in ourselves except the pride that we took in the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry. . . They were our Ralph Bunch, Marian Anderson, Joe Louis, and Jackie Robinson.”

(Arlen F. Fowler. Black Infantry in the West: 1869-1891. Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996, p. 148).

Watch a sample video clip from our documentary

The Frontier Forts and the American Indian Wars in Texas